2025年7月15日,英国皇家建筑师协会官方杂志RIBA Journal发表专栏文章 The power of incremental rejuvenation: the urban regeneration of Xiaoxihu Block, Nanjing 介绍小西湖城市更新经验。文章作者Helen Castle是英国皇家建筑师协会出版与教育内容总监,她于2024年4月9日访问小西湖街区,并在2024年7月1日在英国皇家建筑师协会伦敦总部采访到访的韩冬青教授。

作者认为,南京小西湖街区更新证明了传统社区保护中"审慎渐进式更新"模式的有效性。建筑师们采用了为街区量身定制的城市更新方法——其重点在于恢复传统街巷格局并推动社区参与,而非单纯保护地标性建筑物。过去十年间,这里实施的一系列小规模改造举措产生了叠加效应,产生了不断进化的持续更新。

以下内容首发于The RIBA Journal

原文作者 Helen Castle

The power of incremental rejuvenation:

the urban regeneration of Xiaoxihu Block, Nanjing

In a historic neighbourhood in Nanjing, China, architects have developed a tailored method to urban renewal, focusing on restoring the traditional street pattern and communityparticipation rather than conserving prominent structures.

Traditional houses separated by an alley in Xiaoxihu Block, Nanjing. Credit: Helen Castle

Xiaoxihu Block in Nanjing is a testament to the success of a measured, stepped approach to the conservation of a traditional neighbourhood. Over the last decade, a series of small-scale interventions have been implemented with cumulative effect.

The regeneration programme was initiated as a pilot project in 2015 by the then Nanjing Planning Bureau to urgently address the living conditions in the southern historic district of the city, which was lacking in public services and infrastructure. There were over 3000 inhabitants living in the 4.69-hectare block with a density of 10 m2per capita. Professor Han Dongqing and his team in the architecture department at Southeast University were appointed to lead on planning and design and the Nanjing Historical City Protection and Construction Group on project implementation.

The rapid urbanisation of the historic city of Nanjing

What marks Xiaoxihu Block out is its historic street pattern. It is one of only a few areas of Nanjing that has survived with internal courtyards and alleyways. Though it is one of China’s most significant historic, cultural cities – most apparent in its monumental, 14th-century city walls – much of Nanjing's built heritage has been destroyed.

In the last few decades, rapid urbanisation has been fuelled by a fast-growing economy. As an important port on the Yangtze River, it is a manufacturing hub and centre for service industries, education, innovation and research. It is home to 21 universities, including two of the oldest and most prestigious: Nanjing University and Southeast University.

During the last 40 years, the population of Nanjing’s metro area has quintupled from approximately 2 to 10 million. In the 1980s, the demand on an expanding metropolis for modernisation – new infrastructure, housing and facilities – led to wholesale rebuilding and renewal. With the demolition of the existing urban fabric, much of the street layout and spatial arrangement of the old city was lost.

Site of Xiaoxihu Block, Nanjing. Credit: Hou Bowen

Xiaoxihu Block has been a residential and commercial district for 1,000 years. During the Ming and Qing dynasties – from the 14th to early 20th centuries– it prospered as a centre for trade, artisan activity and imperial examinations.

Workshops and offices were often integrated in courtyard dwellings. Under private ownership, the evolution of the built environment and its social organisation remained stable for many centuries with courtyard houses being the main residential type; detached and terraced houses were only introduced in the first half of the 20thcentury during the Republic of China (1912–49).

After the revolution in 1949, the shift from private ownership to public tenancy led to the subdivision of properties’ use rights, the building of new multi-storey dormitories and the construction of illegal structures in courtyards and alleyways to meet unmet housing need. By the millennium, living conditions had deteriorated significantly within the block.

Most residents used public kitchens and bathrooms. With no connection to mains drainage and electricity, the district’s streets and alleys would flood with rain and sewage. Inhabitants who could afford to moved out, leaving an aged and marginalised community, incapable of maintaining and renovating their homes. When surveyed in 2017, the majority of residents expressed a strong desire for resettlement or reconstruction.

Revitalising the community and built neighbourhood

Thus the regeneration at Xiaoxihu Block has not only been about conserving the historic street pattern, plot organisation and building types, but also maintaining and reviving the social structure, protecting old residents by providing them with the option to stay or leave. It is the first project in Nanjing to adopt a progressive voluntary housing policy.

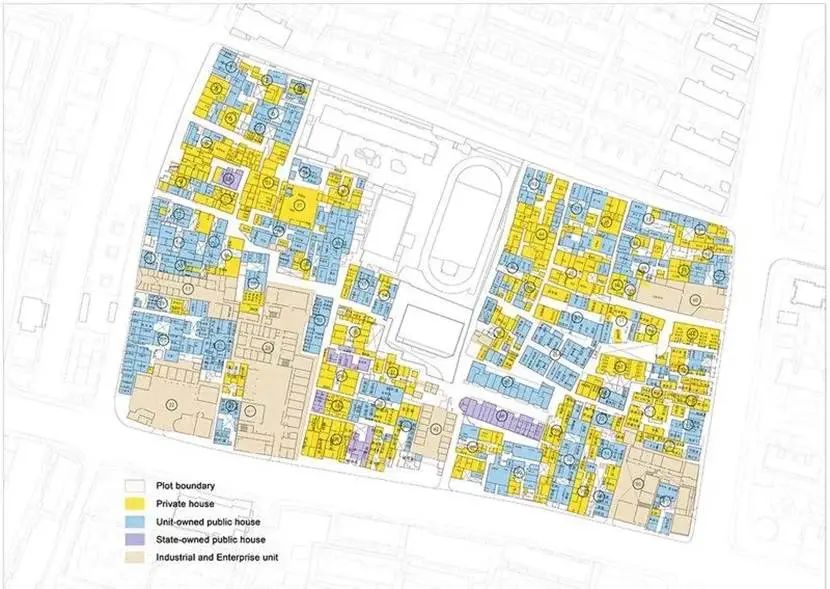

The first two or three years of the scheme were dedicated to community research, exploring property rights with the residents, which resulted in a graphic mapping of ownership of each plot, building and even individual rooms, while also establishing an understanding of the inhabitants’ long-term desires. Out of an original 810 households, by 2022 some 45 per cent (367) remained.

This has enabled the social glue of the neighbourhood to be maintained while also addressing overcrowding. People wishing to leave have been offered resettlement apartments, while a co-living courtyard model was developed for residents who wanted to remain, with kitchens and bathrooms being added. While the government funds public projects, subsidies have been made available to encourage residents to proactively renovate their own homes. Grants meet 40 to 60 per cent of construction costs, depending on how dilapidated a property is.

Property rights typological map: presentation of plots, buildings and rooms. Credit: Southeast University

From 2019 to 2021, the first phase of the project focused on the revitalisation of the block’s main artery, Madao Street—Duicao Alley, and several key plots. At inception, Duicao Alley was occupied by illegal constructions, rendering it narrow and dilapidated. During renovation, the street’s pavement was replaced and street furniture provided, enabling communal life and commercial activity.

The provision of much-needed infrastructure and services was a key step in the regeneration. To avoid the difficulty of burying large mains pipes, the design team developed a micro comprehensive pipe technology. In the middle of the block, an integrated control centre was constructed with an underground fire reservoir, a power substation and a control office was established to support the community.

In addition to the conservation and reuse of historic buildings, further sites were identified for rejuvenation. These included the Blossom Hill Hotel, which was developed out of three existing buildings. Once work had started on site, the ruins of a Taoist temple was discovered and the design strategy for the hotel was reworked to create a floating structure above the foundations.

Besides historical spaces, public, cultural and commercial facilities have been introduced, including a youth apartment, café and bookstore, and most unusually of all, Bug’s Space, a permanent exhibition of insects by artist Zhu Yingchun, that hosts local educational activities. A private courtyard at 33 Duicao Alley, meanwhile, was renovated by the government with the support of its owner, Mr Liu, who now opens it for the benefit of neighbours and visitors.

The first phase of regeneration projects, undertaken 2019–21. Credit: Southeast University

Improving fire safety and addressing sustainability

For the conservation of historic districts in China, which are constructed out of timber structures, fire safety is a principal concern. This has been addressed at Xiaoxihu Block through the provision of an integrated fire protection system and a control centre with a small fire station, comprehensive pipe-gallery and outdoor hydrants. Emergency services are primed to gain access within three minutes. To mitigate the spread of future blazes, rebuilt traditional buildings are erected with non-combustible glulam structures, while more modern ones use steel and concrete.

Prior to the regeneration of the block, the run-down state of the neighbourhood – with its high density of inhabitants and proliferation of illegal structures – were negating the environment benefits afforded by the traditional street pattern and urban fabric. Residents were living in dark, unhealthy and overcrowded conditions.

As part of the conservation programme, streets and alleys have been cleared and public squares reinserted. Alongside the renovation of individual buildings, ventilation and lighting conditions are being improved by reintroducing courtyards and patios. To enhance thermal insulation and energy savings, traditional clay bricks are being replaced by new concrete bubble bricks; moisture-proof and thermal insulation layers are being added to foundations and roof structures.

The holistic approach to regeneration has also been pivotal in creating a more sustainable community. By encouraging the establishment of new small businesses, such as a lantern workshop, home stays, restaurants and cafes, visitors are now being drawn to the area. This has reignited the neighbourhood’s vitality – and pride in its unique cultural heritage.

Duicao Alley renovated with illegal structures removed.Credit: Hou Bowen

Constant evolution: combining the old and the new

For Professor Dongqing, the regeneration of a neighbourhood such as Xiaoxihu Block is about constant evolution: “There is no end point to the project,” he says. “With more residents participating in the renovation of their buildings and community activities, it is only gaining momentum.”

In the year since I visited Xiaoxihu Block, Little West Lake has been constructed, reviving the memory of an ornamental lake on the site that was part of a classical Chinese garden. Meanwhile Zhuqueli bathhouse, a design following the Weng Hall prototype of a 600-year old public bathhouse, is being built to improve the living quality of the residents who lack in toilet facilities at home.

The growing impetus of the initiative is a testimony to the success of Dongqing and his team’s incremental approach, which has taken residents with them. By tactically reasserting the spatial layout of the historic area bit by bit, they have worked with the neighbourhood’s organic character, allowing for the evolution and juxtaposition of buildings from different periods.

The emphasis on revitalising the community, encouraging inhabitants to renovate their homes and develop new small businesses to reinvigorate the district has proved a game changer. Concentrating on the spaces between buildings, rather than the pristine preservation of historic structures, has proved a potent catalyst for the neighbourhood’s rejuvenation.

The reconstruction of Little West Lake revives the memory of an ornamental lake in a Ming Dynasty classical garden. By the early 20th century, the garden was dilapidated and the lake was filled in and covered with housing.Credit: Tang Jun

With thanks to Professor Han Dongqing and Associate Professor Wang Chuan of the School of Architecture, Southeast University, Nanjing.